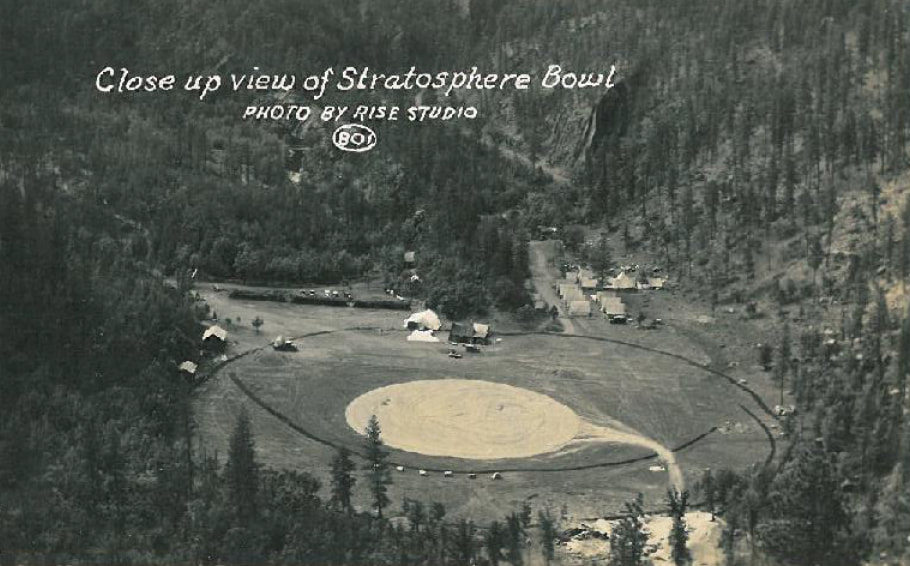

The so-called “Stratobowl” has seen numerous manned balloons launch from its wind-protected confines, but the flights of the high-altitude balloons Explorer I and Explorer II, in 1934 and 1935 respectively, mark the earliest and most groundbreaking of the bowl’s launches. Both Explorer balloons sent Army officers to the stratosphere in hopes of using modern equipment to take photographs and gather other scientific data from a remote and little-studied region. But in addition to collecting data, the missions captured the nation’s interest and showcased the future of aviation technology.

Although Sputnik would not launch for another two decades, a worldwide effort to explore the boundaries of Earth’s atmosphere had already begun in earnest. Three American men active in these exploration efforts, Army officers Capt. Albert Stevens, Capt. Orvil Anderson and Maj. William Kepner, comprised the crew of Explorer I – at the time the largest balloon ever constructed. The bag weighed two and a half tons and contained seven miles of fabric, and when inflated would lift the three officers in an enclosed metal gondola weighing nearly one ton.

At Capt. Stevens’ urging, the National Geographic Society joined the United States Army Air Corps in sponsoring the flight, which was scheduled for the summer of 1934. The crew’s main objective was to gather scientific data from largely unstudied regions of the atmosphere, but this directive did not prevent the flight crew or other officials from entertaining the prospect of setting an official altitude record.

The decision to launch Explorer from Moonlight Valley was met with fervor in Rapid City as locals prepared to stage a grand event for citizens from around the country. According to the Denver Post, South Dakota Gov. Tom Berry and his wife became “enthusiastic stratosphere fans.”

The excitement was not contained to South Dakota, though, as tourists filed into Rapid City “by the thousands.” Adding to the anticipation of the flight, some scientists claimed that data gathered during the flight would allow the country’s farmers to anticipate droughts and other natural phenomena by predicting weather one year in advance.

As the U.S. Army Air Corps ground crew readied the Stratobowl and Rapid City community members prepared the town, weather became the mission’s sole cause for delay. Throughout most of July 1934, the crew waited for calm winds and clear skies.

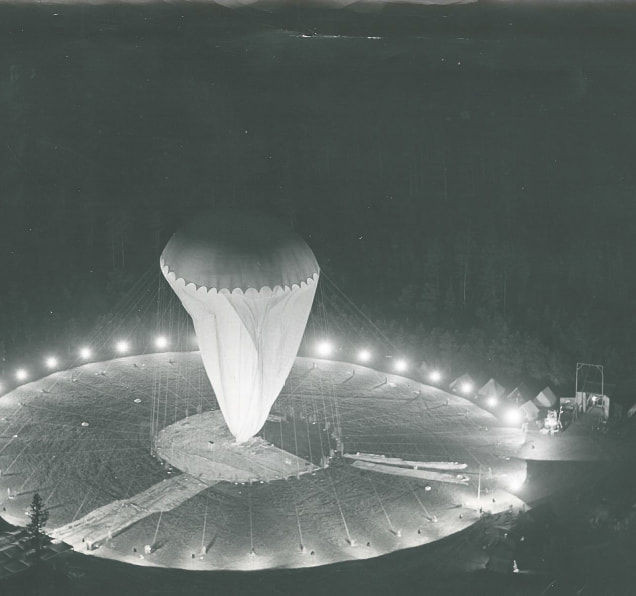

After weeks of anticipation, weather forecasts came back positive and at 5:45 a.m. on Saturday, July 28, the balloon officially released from its tethers and began its journey. Multiple estimates reported that 50,000 people gathered on the cliffs above the balloon to watch it take off. Despite witnessing a trouble-free inflation and departure, onlookers would later learn of Explorer’s shocking and unplanned return to earth.

Upon reaching an altitude of approximately 60,000 feet, the flight crew noticed a 30-foot rip in the underside of the balloon. This structural failure led to a rapid escape of gas from the torn balloon, which soon began to resemble a giant parachute keeping the gondola from plummeting to earth. The crew bailed after sinking several thousand more feet, as the balloon had ripped beyond repair and the gondola had begun hurtling toward earth at near-free-fall.

Witness M.C. Boyer, a government engineer who aided the crew with salvage operations after the crashing landing, said the sound of gas escaping the balloon “could be heard for five miles.”

Two days after the crash, Capt. Anderson described the mood of the crew as the balloon descended, saying, “If there was hope among us of getting down safely, it was a remote one.” Despite this despair, all three crew members parachuted to safety and managed to save the spectrograph, an important instrument was used to study cosmic rays.

The near-fatal mission did not discourage the crew members or the sponsors. Within days of Explorer’s accident, the National Geographic Society had already made public its hope for another stratosphere flight.

One year later, Explorer II was preparing a summer launch from the Stratobowl, but the balloon fabric ruptured during inflation. Unfazed, the crew hoped to make a third attempt at a successful stratosphere mission. On August 20, 1935, just over one month after Explorer II failed to inflate, the order was given for another attempt, this time planning on an October liftoff. As with Explorer I, the anticipated launch of Explorer II generated much enthusiasm. Nearby schools even ordered a holiday for the day of the balloon’s inflation.

At 7 a.m. on November 11, 1935, with temperatures in Rapid City hovering in the single digits, Explorer II attempted to take flight for a second time. Similar to the scene for Explorer I, 50,000 spectators witnessed Explorer II lift off smoothly. But unlike the mission in 1934, Explorer II accomplished all of its scientific goals and landed safely and intact 230 miles east of Rapid City, near White Lake, S.D.

The crew even set an official altitude record, ascending over 74,000 feet above the earth. The success of Explorer II was considered worldwide to be an aeronautical milestone, and newspaper headlines on the balloon’s mission shared top coverage with the assassination of American senator Huey Long and the Italian-Ethiopian War. The United States military also celebrated the mission, as acting Secretary of War Harry H. Woodring said “The pioneering efforts have the gratitude of the war department which seeks to make our air force the greatest in the world.”

The full effect of the technology developed for Explorer II, however, would not be realized for another decade following its flight. After the Second World War, Woodring’s words carried new meaning as the U.S. Army Air Forces used technologies in B-29 Super Fortresses that were developed for and studied in Explorer II. H.H. Arnold, commanding general of the Air Force during World War II, said following conclusion of the war that Explorer II “bore fruit in World War II far in advance of what was imagined to be the results of the time.”

Both Explorer I and Explorer II brought hope and excitement to the Black Hills not seen since the gold rush, but their failures and successes did much more than generate tourism. Their ascent into the stratosphere built national pride, expanded scientific knowledge, and ultimately represented a significant step in the ever-growing evolution of human flight.

Today, the Stratobowl is a popular hiking spot in the Black Hills with a fantastic view from the Stratobowl Rim Trail. A plaque memorializing the lauches in the 1930s is set at the end of the trail on a stone outcropping, along with informational panels nearby. Crowds flock to the Stratobowl every September to watch hot air balloons lift off from the historic site.

You can view more photos of the "Stratobowl" in our digital archives.